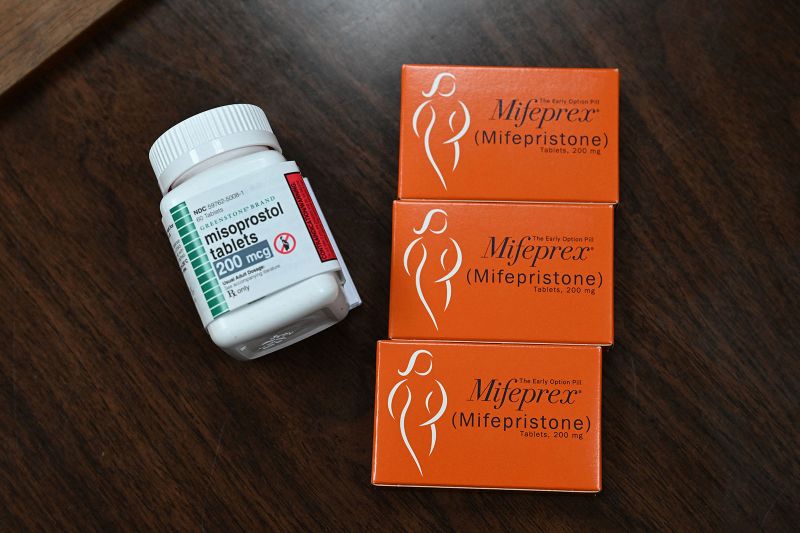

Louisiana’s first-in-the-nation law listing the abortion medications mifepristone and misoprostol as “controlled dangerous substances” took effect Tuesday, triggering fears among health-care providers and pharmacists that routine care may be worsened for women in the state.

Beyond abortion, the medicines are used for miscarriage management and, in misoprostol’s case, to stop dangerous bleeding after childbirth, physicians say. Now, in Louisiana, misoprostol is required to be stored in a locked box like other controlled substances, which doctors fear could delay treatment in emergency situations.

“You want to be able to have it right there in the moment,” said Dr. Jennifer Avegno, an emergency physician and director of the New Orleans Health Department.

She said health-care providers in the state have been doing drills to see how long it will take to get misoprostol from locked cabinets in emergencies during childbirth.

“It adds several minutes to that process,” she said. “If you’ve ever watched someone bleed out after childbirth, as I have, you know that minutes can make a difference.”

Abortion was already illegal in Louisiana, with narrow exceptions. Gov. Jeff Landry, on signing the bill, said it would protect women across the state. Possessing the medicines without a valid prescription could now come with penalties of up to five years in prison and a fine of up to $5,000, although the law specifically exempts pregnant women who possess the drugs “for her own consumption.”

The law, passed in May, puts mifepristone and misoprostol in the same category in Louisiana as benzodiazepines including Valium, Xanax and Ativan. It was proposed by Republican state Sen. Thomas Pressly after he said his sister had been given misoprostol against her will, and it established the crime of “coerced criminal abortion by means of fraud.”

Fears over timely treatment

Mifepristone and misoprostol are the regimen used for medication abortion, now the most common way people access abortion in the United States. Mifepristone blocks progesterone, a hormone needed for continuing a pregnancy, and misoprostol causes the uterus to contract, leading to cramping and bleeding.

For miscarriages, they are used in emergency settings when patients are having complications and for outpatient care.

“One of the most common reasons that people choose medication management of a miscarriage is because they want timely treatment and to put the process behind them as soon as possible,” said Dr. Honor MacNaughton, a family physician with expertise in reproductive health at Cambridge Health Alliance in Massachusetts. “A lot of people don’t want to wait to be scheduled for the procedure or wait for the miscarriage to happen on its own, since that process can take days or sometimes even weeks.”

Dr. Anitra Beasley, medical director of Planned Parenthood Gulf Coast, which has two clinics in Louisiana, said she worries that the law’s new restrictions could mean patients can’t get timely access to the medicines, because doctors could be afraid to prescribe them or pharmacists could be afraid to fill the prescriptions. Patients legally prescribed the medicines for miscarriage care could also be confused about whether it’s legal to take them, she said.

“Knowing that you have a pregnancy that has ended and wanting to medically manage that process and being told you that you can’t, or having to travel through parish to parish to parish trying to find someone who’s going to give you the appropriate medications,” Beasley said, “I just can’t imagine how much heartache that person must have at that particular point.”

Proponents of the law argue that it doesn’t affect legal prescriptions of the medications, and the Louisiana Department of Health issued guidance for health-care providers in September seeking to clarify that the medicines can be used in hospitals to treat postpartum hemorrhage and incomplete miscarriages. It said the medicines should be stored in a locked cabinet.

Large health systems and pharmacy organizations said they have been preparing for the law to go into effect for months. Ochsner Health, a major health system in the state, issued a set of answers to frequently asked questions for its staff last week, addressing which providers can prescribe misoprostol, how to order the drug and what steps will be required to access it from a locked drawer.

“Beginning Oct. 1, 2024, providers in all specialties will need to follow the controlled substance patient record documentation process,” the guidance says. Prescribers will need to specify why the medicine is being prescribed, or the electronic health record system won’t allow the prescription to go through, it says. It also notes that there will be an override system to allow misoprostol to be released from the locked cabinet in emergencies.

‘Misusing the schedule system’

Doctors in addiction medicine said that characterizing these drugs as controlled substances is an overreach of what the scheduling system aims to do. Requiring misoprostol and mifepristone to be stored the same way as sedatives such as benzodiazepines, “frankly, is absurd,” said Dr. Lucille Howard, an ob/gyn who is an addiction medicine fellow at Tulane University in New Orleans. “They just don’t have that same potential for dependence or addiction at all.”

It’s “misusing the schedule system,” added Dr. Smita Prasad, president of the Louisiana Society of Addiction Medicine and an assistant professor at Tulane. “It also really deflects from a real problem that we have in the United States: other substances like fentanyl and synthetic fentanyl, that are killing people.”

Scheduling the drugs also requires that their use be tracked by a Prescription Drug Monitoring Program, “a statewide program where I can look for a patient under my care and I can see for the past 15 years if they’ve been prescribed any scheduled medications, who the prescriber was, where they filled that medication,” and information about dates and amounts used, Prasad said.

It was a system designed to curb opioid abuse, said Anna Legreid Dopp, senior director of government relations for the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, but her organization’s members expressed concern that it could stigmatize patients who were legally prescribed mifepristone and misoprostol, a concern shared by physicians.

“Every time one of our physicians writes a misoprostol prescription, that’s going to be documented,” said Avegno, the director of New Orleans’ health department. “There is a real fear that someone is going to say, ‘Oh, that OB wrote 20 prescriptions last month. I wonder if they’re secretly doing abortions. I’m going to investigate,’ right?”

Dopp’s organization, which represents pharmacists working at hospitals and other health-care facilities, revised its policy after Louisiana’s law was passed to oppose rescheduling medications used for reproductive health and reporting of those medications into prescription drug monitoring programs.

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Friday from the CNN Health team.

“Almost immediately, our members raised concern that if this is being done in one state, it can easily be a template for other states to use it,” Dopp said.

Louisiana, which has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the country, has made hard-won progress over the past decade in reducing deaths from postpartum hemorrhage, Avegno said.

“Now we’re adding a reason for postpartum hemorrhage to go back up,” she said. “It really violates the standard of care that our OBs are used to practicing.”

The New Orleans City Council directed the health department to study the effects of the law, Avegno said, and her team has set up an online form for patients, pharmacists and medical providers to share their experiences confidentially.

“Really just to document what is occurring so we can bring that to our decision-makers and say, ‘Look, these are the consequences,’” Avegno said. “We don’t want anybody to suffer in silence and feel like not being able to access care is something that no one cares about. Because we certainly do.”